Digital platforms providing intermediation services are becoming increasingly popular and disruptive in a variety of industries. Those services may qualify merely as “information society services”, while in other occasions, they are regarded as ancillary to an overall service coming under a different legal classification, triggering the implementation of different set of rules.

Background of Airbnb case

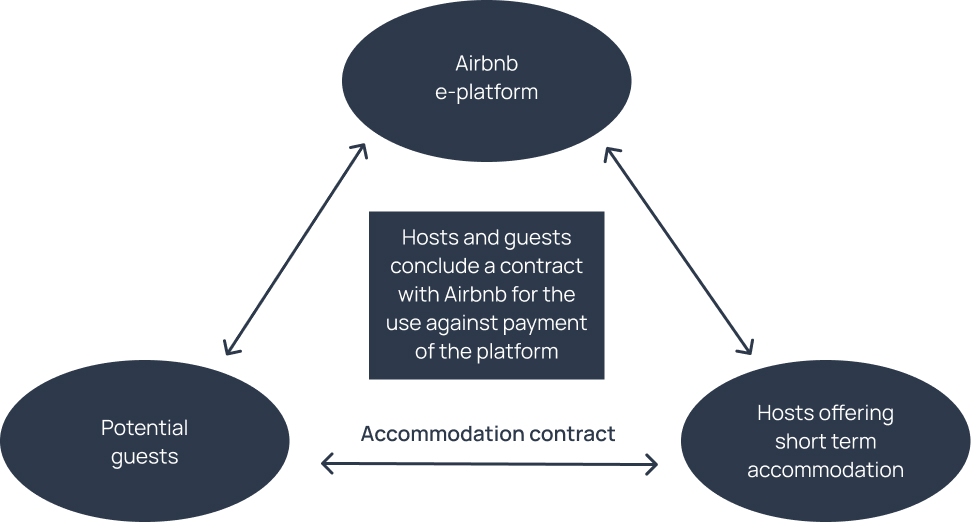

In January 2017, AHTOP, the French Association for professional tourism and accommodation, lodged a criminal complaint in France against Airbnb “for the practice of activities concerning the mediation and management of buildings and businesses without a professional licence”, according to the relevant French law (Hoguet law). In support of its complaint, AHTOP claimed that Airbnb Ireland did not merely connect two parties (guests and hosts) through its platform, but also offered additional services which amounted to an intermediary activity in property transactions. On the other hand, Airbnb denied acting as a real estate agent and argued that the Hoguet Law is inapplicable on the ground that the service provided by Airbnb should be classified as an “information society service” within the meaning of Article 2(a) of Directive 2000/31/EC (“E-Commerce” Directive)1 (“any service normally provided for remuneration, at a distance, by electronic means and at the individual request of a recipient of services”) and, therefore, Airbnb can avail itself of the so-called “country of origin” principle under the E-Commerce Directive

Findings of the Court in case C‑390/18

In its recent decision, the ECJ first confirmed that the service provided by Airbnb constitutes in principle an information society service within the above meaning, since it meets the four cumulative conditions of the definition, i.e. the service is provided i) for remuneration, ii) electronically, iii) at a distance and iv) at the individual request of the recipients of the service.

Then, the Court examined whether, the above intermediation service forms an integral part of an overall service whose main component is a service coming under another legal classification, notably accommodation service (falling under the notion of ‘service’ in Directive 2006/123), thus not classifying as information technology service, as ATHOP maintained.

In that respect, the Court reached the conclusion that the essential feature of the electronic platform managed by Airbnb Ireland is the creation of a structured list of the places of accommodation available and the compiling of offers using a harmonized format, coupled with tools for searching for, locating and comparing those offers. According to the Court, this service cannot be regarded as merely ancillary to an overall service coming under a different legal classification, namely provision of an accommodation service.

Further, the Court considered two negative conditions in support of the above finding: i) a service such as the one provided by Airbnb Ireland is in no way indispensable to the provision of accommodation services, since both guests and hosts have a number of alternative channels at their disposal (such as real estate agents, classified advertisements etc.) and ii) Airbnb Ireland does not set or cap the amount of the rents charged by the hosts using that platform (at most, it provides them with an optional tool for estimating their rental price having regard to the market averages taken from that platform).

In addition, the ECJ analyzed a series of features commonly used by digital platforms which, even taken together, do not call into question the separate nature of the intermediation service provided by Airbnb and therefore its classification as an ‘information society service’:

▪ Tools to hosts and guests. The platform provides hosts with a format for setting out the content of their offer, an optional photography service for the rental property and a system for rating hosts and guests which is available to future hosts and guests. For the ECJ “such tools form part of the collaborative model inherent in intermediation platforms, which makes it possible, first, for those seeking accommodation to make a fully informed choice from among the accommodation offerings proposed by the hosts on the platform and, secondly, for hosts to be fully informed of the reliability of the guests with whom they might engage”.

▪ Collection of payment by the platform. According to the ECJ “such payment conditions, which are common to a large number of electronic platforms, are a tool for securing transactions between hosts and guests, and their presence alone cannot modify the nature of the intermediation service, especially where such payment conditions are not accompanied, directly or indirectly, by price controls for the provision of accommodation”.

▪ Offer to hosts of guarantee against damage and, as an option, civil liability insurance.

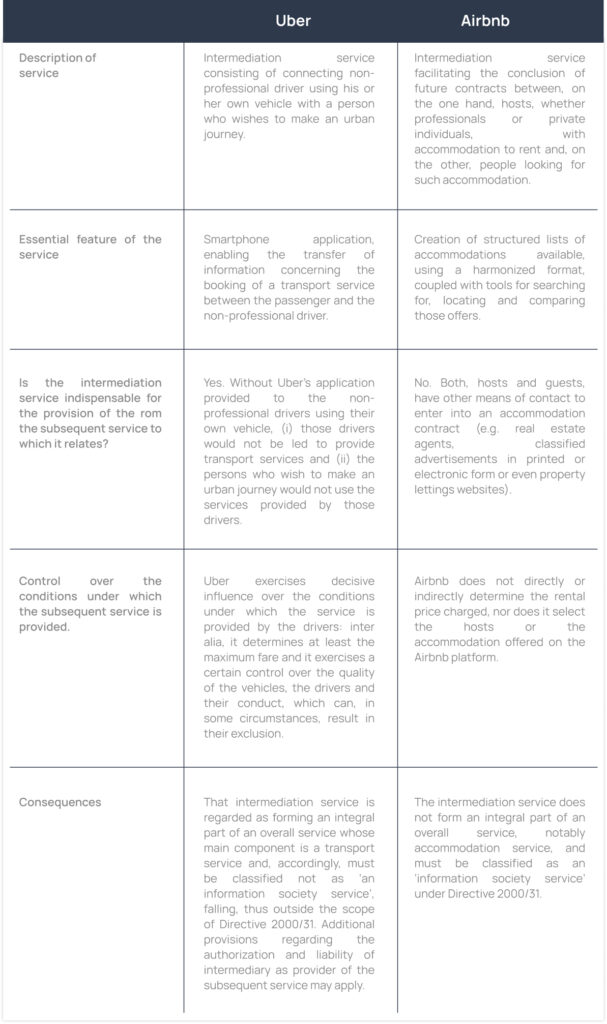

Moreover, the ECJ clarified that the findings in the case in hand could not be equated to those in previous Uber cases (C-434/15, C‑320/16), since, apart from the fact that the services in those cases are not comparable, Uber exercises decisive influence over the conditions under which transport services are provided by the non-professional drivers using the application made available to them by that company, which is not the case with Airbnb, particularly since Airbnb Ireland does not determine, directly or indirectly, the rental price charged, nor does it select the hosts or the accommodation put up for rent on its platform.

Finally, the Court found that the provisions of Hoguet Law, insofar as they restrict the freedom to provide information society services, cannot be applied to an individual in a situation like that of Airbnb Ireland , given that France failed to fulfil its obligations under the second indent of Article 3(4)(b) of Directive 2000/31, by not notifying the Commission and the Member State on whose territory the service provider in question is established, of its intention to adopt the restrictive measures concerned.

Conclusion

Although the qualification of an intermediary service provided through an electronic platform as ‘information society service’ remains in essence a factual issue, the ECJ ‘s conclusions in the aforementioned cases provide a useful tool when analyzing the applicable legal framework on different business models of the platform economy. Below is comparative table with an overview of the key findings in Uber and Airbnb cases.

1 Referred to in point 2 of the first paragraph of Article 1 of Directive 98/34 and then, as of 7 October 2015, in Article 1(1)(b) of Directive 2015/1535.

© Logaras Law (2023). All contents on this website, including logos, trademarks, texts, newsletters and articles (hereinafter the “Contents”), are protected under intellectual property law. Except where otherwise stated, use, downloading, reproduction and distribution in whatever form and by whatever medium (including Internet) for whole or part of the Contents available on this website and newsletter is not authorized.